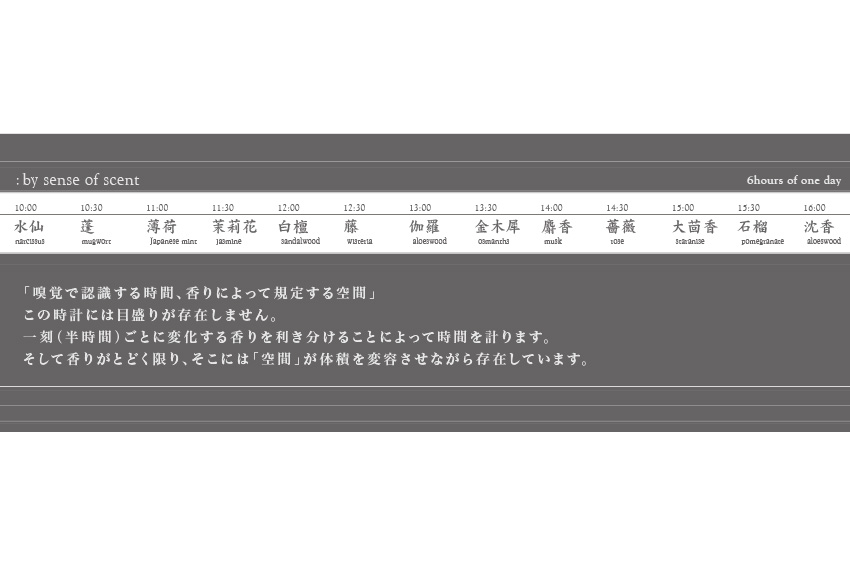

: by sense of scent

「嗅覚で認識する時間、香りによって規定する空間」

この時計には目盛りが存在しない。

一刻(半時間)ごとに変化する香りを聞き分けることによって時間を意識する。

そして香りがとどく限り、そこには「空間」が体積を変容させながら存在している。

◆時間とはなにか?

現代に生きる私たちは、朝から夜まで、寝ている間でさえも「時間」を無視して生活していくことはできない。

産業を発展させ、情報伝達を加速させ、移動時間を飛躍的に短縮させてきた私たち。

手のひらに収まるほど小型化された先進機器によって、100分の1秒、1,000分の1秒単位で時間を知ることができるようになった。

しかしそれと引き換えに私たちが獲得しているのは、その短縮化が目標とされ、最終的には否定されるべき対象としての時間である。

考えてみれば私たちは時計なしの時間を知らない。もっと言えば、数字以外での時間の認識方法を知らないのである。

時を見た人はいないのに、時計に時を見せられて、急かされながら現代社会のなかで生活をしている。

人間らしい暮らしに、はたして秒単位で時間を知る必要があるのだろうか?

◆共有する

時間を確認する手段は時代とともに進化してきた。

100年前に遡ると、人々は教会の時計台や寺院の時鐘で時刻を知った。地域で一つの時間を共有していた時代である。

50年を経ると、家庭に掛け時計が登場し、決まった時間に家族揃ってテレビの前に集まるという、家族単位での時間共有に移り変わる。

そして今は、安価な腕時計や携帯電話で誰もが正確な時間を確認できるようになった。個人で時間を管理する時代である。

町や村に一つから家庭に一つ、そして一人に一つ。時計をもつ単位が変わり、それによって時間を誰が管理するのかが変わり、人々の生活も集団から個へと変化した。

私たちは、そのおかげで幸せになれただろうか?

共同体の中で時間を感じ取っていた時代に比べ、個々の時間で行動する現代は、家族が一つの食卓を囲むことさえも難しくなっている。

◆時を刻む

最古の時計の記録は、紀元前4000〜3000年ごろにさかのぼる。古代エジプトで考案された日時計が第一歩とされている。

この時代の時計は天文や占星術と関わりが深く、「神の領域」として扱われるものであった。

日本では、古代〜室町時代までは定時法が使用された。

『延喜式』(905年〜927年にかけて編纂)や『枕草子』(996年頃成立)などに出てくるこの時法は、1日を十二支を配した12辰刻に等分して、1辰刻をさらに4刻に等分した1日48刻(12辰刻×4刻)の「四八刻法」という定時法が主に使用された。

※ 四八刻法

1日=12辰刻=48刻=480分(ぶ)・・・ 現代の24時間=1,440分=86,400秒

1辰刻=4刻=40分(ぶ)・・・・・・・・・ 現代の2時間=120分=7,200秒

1刻=10分(ぶ)・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 現代の30分=1,800秒

1分(ぶ)・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 現代の3分=180秒

◆嗅覚によって

現代社会に於いて、人間らしい暮らしを取り戻すために必要な時間認識の最小単位を、一刻(30分)と規定した。

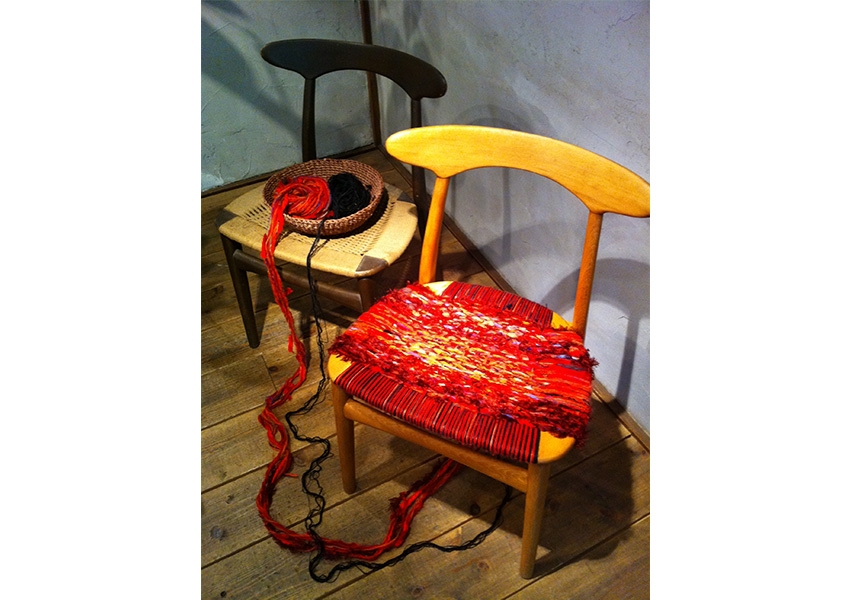

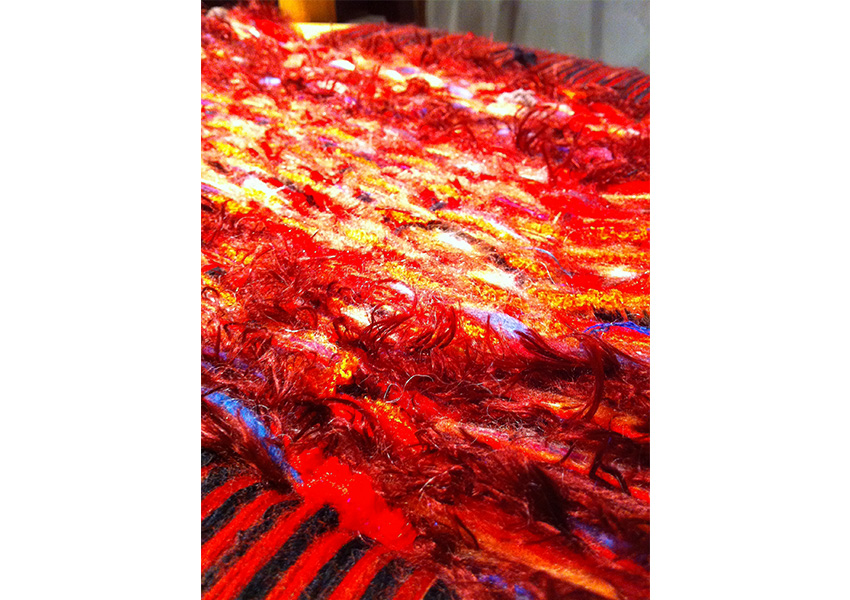

この時計には、目盛りが存在しない。だいたい一刻ごとに変化する線香の香りを利き分けることによって、時間を認識する。

江戸時代にはお香が燃える速さで時刻の経過を知る「香盤時計」があったくらい精度は安定していて、8時間を計っても誤差は ±10分程度である。

何時にどんな香りがするのかという情報さえ伝えておけば、脳内の記憶と感情の分野に強く作用し、五感の中でも最も野生に近い感覚と言われる嗅覚によって、一週間もすれば体が覚えてしまう。

動物の感覚というのは、本来はそれくらい確実なものである。

◆空間を規定する

本来は見えない時間を見えるようにした現代の時計と、この時計では「時間」の定義は本質的に異なる。

享受できるのは積み重ねられた時間であり、人間らしい生活に寄り添う速度で流れる時である。

「古くて新しい時間」の概念は、私たちを縛り付け、短い方が良しとされた「時間」から私たちを解き放つだろう。

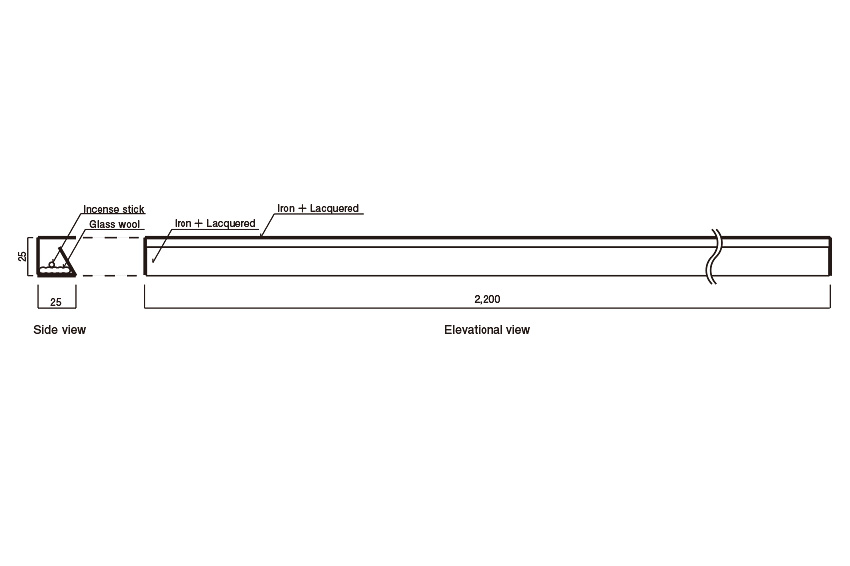

そして、まるでモノリスのような形態のこの時計は、視覚ではなく嗅覚に訴えかけるためにデザインされている。

つまり見えなくても良いデザインなのである。

この物体が放つ香りは縦横無尽に拡散し、時を知らせ、とどく限りそこには「空間」が容積を変容させながら存在する。

視覚や触覚に頼らない空間認識の方法でもある。

This timing devise doesn’t have any scales.

It is a devise that gives an experience of “old-new time” by dispersing different scents every thirty minutes.

We, the modern day species, cannot live from dawn to dusk and even while asleep without being conscious of time.

We developed industries, accelerated the speed of information and shortened the time of transportation dramatically.

We measure time in the scale of one in the hundredth, or even in thousandth, with a high-tech device that fits in our palms.

Yet, what we gain in the end is the very time that is the object of reduction and ultimately denial.

If you think about it, we don’t know any other concept of time beside the one we know from what we call clock or watch.

In other words, we don’t know how to recognize or feel the concept of time without numbers.

We spend everyday being rushed, mostly because watches on our wrists and clocks on the walls show us what we think is “time”, a widely shared concept, not an object, nobody has seen.

Do we really need to know time by the seconds if we ought to thrive for dignified human life?

The means by which we check the time has evolved over the years.

About a century ago, people were told what time of the day it was by church towers and temple bells.

It was an era when the concept of time was shared locally.

Half a century later, clocks on walls inside houses made the concept of time sharable among members of a family unit so that they can gather in a living room at a fixed time to watch television.

And now we own individual wrist watches and cell phones that tell precise time at any given moment.

It is an era we manage our own concept of time.

The unit of the installment of a timing device has been shifted from towns or villages to families then individuals.

The shift of the unit in which timing device is installed changes who manages the time, thus the unit of daily lives shifted from group operations to individual operations.

Did the shift make us happier?

It certainly became harder nowadays for a family unit to sit at the same table for a meal; something we took much smaller effort to do when time was managed and shared by groups rather than individuals.

The first invention of timing devise on record goes back 4000 to 3000 B.C.

A sundial invented in ancient Egypt is considered to be the very primitive form of a timing devise.

Timing devises back then had great deal with astronomy and astrology, something to be respected as “field of God”.

In Japan, the fixed time method was installed in society from ancient times to Muromachi period (1333–1573 A.D.).

The fixed time method mentioned in ancient literatures such as “Engi-Shiki”(set of ancient Japanese governmental regulations compiled from 905 to 927 A.D.) and “The Pillow Book” (completed about 996 A.D.) was a time system or chart of sort that divided a day into twelve Tatsutoki periods based on the twelve horary signs, then divide a Tatsutoki period into four Toki periods, thus making a full day consisted of 48 Toki periods.

Forty-Eight-Toki Chart

A full day = 12 Tatsutoki = 48 Toki = 480 Bu・・・GMT 24 Hours = 1,440 Minutes

1 Tatsutoki = 4 Toki = 40 Bu・・・・・・・・・・GMT 2 Hours = 120 Minutes

1 Toki = 10 Bu・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・GMT 30 Minutes

We’d like set the minimum unit of time in order for us living in a modern society to restore dignified human life is one Toki (30 minutes), thus propose a devise that does not tell or show time, but rather a timing devise that lets us recognize time.

This devise lets us recognize time by dispersing scents every Toki period (thirty minutes) as an incense stick made of different ingredients installed inside is being burnt.

Record shows that incense clocks were in use during ancient times that told time by the speed of incense being burnt.

This proposed incense clock operates with accuracy of ±10 minutes margin of error after 8 hours.

It will probably take less than a week to condition one’s body and mind to operate with this method if one is given information about what scent comes when, based on the fact that among the five human senses the sense of smell still remains to be close to wild and primitive state.

It would once again remind us that all senses in animals are that much accurate and reliable.

There is a fundamental difference in the definition of time between modern timing devise that made originally invisible concept visible, and the incense clock that does not “show” the concept.

What we gain will not be pieces of time in minutes and hours, rather, accumulated layers of time that flows at a rate of dignified human life.

The invention of “old-new time” would set us free from the concept that tied us to schedules and rushed us on timetables.

Therefore, the incense clock resembling the shape of monolith is a clock that appeals to the sense of smell, not visual.

In short, the design of this clock is free of visual appeals.

Scent generated from this closk disperses, tells time and evolves its capacity as it reaches to those who operate based on sense of smell.

It is also a way to recognize a space without relying on senses of visual or touches.